Rainbow Body

Emptiness, Dependent Origination, Compassion and Sambhogakāya.

In a review of “Rainbow Body and Resurrection” by Michael Sheehy, the author writes: “In Dzogchen cosmology, the cosmos is envisioned as being utterly open and translucent. Movement ensues when the element of air stirs up wind that oscillates rapidly into fire; from fire emerges water, and from water, the solidity of rock and earth are stabilized. With this gravitational collapse into the elemental forces that comprise the cosmos, a spiraling reconfigure matter into worlds wherein embodied beings form.” Think of high vibratory states slowing down until they become dense matter.

From that view, all that

we perceive, including our own bodies, is formed by the “Legos,” or building

blocks of reality — earth, water, fire, air, and space. The rainbow reference

comes from the colors of the elemental lights; white (space), red (fire), blue

(water), green (wind or air), and yellow (earth).

As Sheehy says, “Under

certain circumstances, the cosmic evolutionary process of matter’s gravitational

collapse into solidity can turn itself back into a swirling radiating

configuration. Tibetan traditions suggest that meditative technologies can

reverse this process of collapse,” or journey from high-vibratory energy to

dense matter. In other words, successful Dzogchen practitioners can reverse the

manifestation process, refining dense matter to pure light/energy.

In other words, successful

Dzogchen practitioners can reverse the manifestation process, refining dense

matter to pure light/energy.

Certain Buddhist meditation practices are meant to alter the gravitational field

of these five elements that constitute the body, transforming them into the five

radiant lights of the color spectrum.

The Tibetan name given to

this physical fluorescence is jalu, literally meaning, “rainbow body.” Rainbow

body is also the name given to the transformation of the ordinary physical body

as a result of years of specific disciplined practices.

Transference is a possible

path.

Radiance is the way.

Rinpoche made it clear,

though, that all these miracles are signs of “the same supreme accomplishment.

Their attainments are exactly equal. These practitioners have attained Buddha in

this very life,” he wrote. Any merit gained by the dissolution of karma is

dedicated to the benefit of the “other” rather than the self. “Miraculous”

activities, such as passing through walls, leaving foot and handprints in stone,

reviving the dead, and appearing in multiple locations at the same moment, are

considered mere “by-products” of accomplishment; they are not the point, only

signs along the way.

To become infatuated with

these powers is to risk pride and arrogance. True Dzogchen practitioners hide

their accomplishments to avoid attention and distractions. Chasing these

abilities, or siddhis, without compassion and dedication to the freedom of all

beings, borders on sorcery — the pursuit of supernatural powers for the benefit

of self.

So if Conscience is still missing, start working on Your soul and You shall follow the right path. La conscience présente certains traits caractéristiques qui peuvent notamment inclure : rapport ŕ soi, subjectivité (la conscience que l'individu possčde de lui-męme est distincte de celle d'autrui), la structure phénoménale, la mémoire, la disponibilité (ou liberté de la conscience ŕ l'égard des objets du monde), la temporalité, la sélectivité, l'intentionnalité.

conscience (n.)

c. 1200, "faculty of knowing what is right," originally especially to Christian

ethics, later "awareness that the acts for which one feels responsible do or do

not conform to one's ideal of right," later (late 14c.) more generally, "sense

of fairness or justice, moral sense."

This is from Old French conscience "conscience, innermost thoughts, desires,

intentions; feelings" (12c.) and directly from Latin conscientia "a joint

knowledge of something, a knowing of a thing together with another person;

consciousness, knowledge;" particularly, "knowledge within oneself, sense of

right and wrong, a moral sense," abstract noun from conscientem (nominative consciens),

present participle of conscire "be (mutually) aware; be conscious of wrong," in

Late Latin "to know well," from assimilated form of com "with," or "thoroughly"

(see con-) + scire "to know," probably originally "to separate one thing from

another, to distinguish," related to scindere "to cut, divide," from PIE root *skei- "to

cut, split" (source also of Greek skhizein "to split, rend, cleave").

The Latin word is probably a loan-translation of Greek syneidesis, literally "with-knowledge."

The sense development is perhaps via "to know along with others" (what is right

or wrong) to "to know right or wrong within oneself, know in one's own mind" (conscire

sibi). Sometimes it was nativized in Old English/early Middle English as inwit.

Russian also uses a loan-translation, so-vest, "conscience," literally "with-knowledge."

RAINBOW BODY TRANSMUTATION

ACCOMPLISHED TRANSMUTATION

Rainbow body (Tib. འཇའ་ལུས་,

ja lü; Wyl. 'ja' lus) — fully accomplished Dzogchen practitioners can dissolve

their body at the time of death.

Through the practice of

trekchö, the practitioner can attain the so-called ‘rainbow body’, in which the

body becomes smaller and smaller as it dissolves, emanating rainbow light, and

finally only the hair and nails are left behind.

Through the practice of

tögal, the practitioner can dissolve his or her body into the ‘Light Body’ (Tib.

འོད་སྐུ་, ö ku),

where the body transforms into light and disappears completely into space. This

was done by Garab Dorje, Manjushrimitra, Shri Singha, Jnanasutra and Vairotsana.

Another accomplishment of

tögal practice is the ‘Rainbow Body of Great Transference’ (Tib.

འཇའ་ལུས་འཕོ་བ་ཆེན་པོ་, ja lü phowa chenpo; Wyl. 'ja lus 'pho ba chen po),

where the master dissolves his body into rainbow light and lives for centuries

in order to benefit others. Such was the case with Padmasambhava, Vimalamitra,

Nyang Tingdzin Zangpo and Chetsün Senge Wangchuk.

In Dzogchen, rainbow body

(Tibetan: Jalü or Jalus (Wylie 'ja' lus) is a level of realization.

This may or may not be accompanied by the 'rainbow body phenomenon'.

The rainbow body phenomenon has been noted for centuries, including the modern

era.

Other Vajrayana teachings also mention rainbow body phenomena.

In Dzogchen

The rainbow body

phenomenon is a third person perspective of someone else attaining complete

knowledge ( rigpa ).

Knowledge is the absence of delusion regarding the display of the basis.

Rigpa has three wisdoms, two of which are kadag and lhun grub. Kadag (

primordial purity ) is the Dzogchen view of emptiness.

Lhun grub ( natural formation ) is the Dzogchen view of Dependent origination.

Throughout Mahayana, emptiness and Dependent origination are two sides of the

same coin.

Kadag deals with tregchöd.

The lhun grub aspect has to do with esoteric practices, such as (but not limited

to) Thödgal, that self-liberate the dependently originated human body into the

Sambhogakāya ( rainbow body phenomenon ). The symbol of Dzogchen is a Tibetan A

wrapped in a thigle. The A represents kadag while the thigle represents lhun

grub. The third Wisdom, thugs rje ( compassion ), is the inseparability of the

previous two wisdoms.

The ultimate fruition of

the thodgal practices is a

body of pure light,

called a rainbow body (Wylie 'ja' lus, pronounced Jalü.)

If the four visions of thogal are not completed before death, then at death,

from the point of view of an external observer,

the following happens: the corpse does not start to decompose, but starts to

shrink until it disappears.

Usually fingernails,

toenails and hair are left behind (see e.g. Togden Urgyen Tendzin, Ayu Khandro,

Changchub Dorje.)

The attainment of the rainbow body is typically accompanied by the appearance of

lights and rainbows.

Some exceptional practitioners such as Padmasambhava and Vimalamitra are held to

have realized a higher type of rainbow body without dying.

Having completed the four visions before death, the individual focuses on the

lights that surround the fingers.

His or her physical body

self-liberates into a nonmaterial body of light ( a Sambhogakāya ) with the

ability to exist and abide wherever and whenever as pointed by one's compassion.

The title of Rainbow Body

by Chitra Ganesh refers to an elevated state of, or metaphor for, the

consciousness transformation known as a rainbow body. The Buddhist master

Padmasambhava achieved this state from his union with Mandarava, a female spirit

(dakini) and princess in Tantric Buddhism. Through study and physical

connection, each played a key role in the other’s enlightenment.

Sambhogakāya

Sambhogakāya is a "subtle body of

limitless form". Buddhas such as Bhaisajyaguru and Amitābha, as well as advanced

bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteśvara and Manjusri can appear in an "enjoyment-body."

A Buddha can appear in an "enjoyment-body" to teach bodhisattvas through

visionary experiences.

Those Buddhas and Bodhisattvas manifest themselves in their specific pure lands.

These worlds are created for the benefits of others. In those lands it is easy

to hear and practice the Dharma. A person can be reborn in such a pure land by

"the transfer of some of the huge stock of 'merit' of a Land's presiding Buddha,

stimulated by devout prayer."

One of the places where the Sambhogakāya appears is the extra-cosmic realm or

pure land called Akaniṣṭha. This realm should not be confused with the akanistha

of the pure abodes, for it is a realm that completely transcends it.

Absolutely seen, only Dharmakāya is real; Sambhogakāya and Nirmāṇakāya are "provisional

ways of talking about and apprehending it."

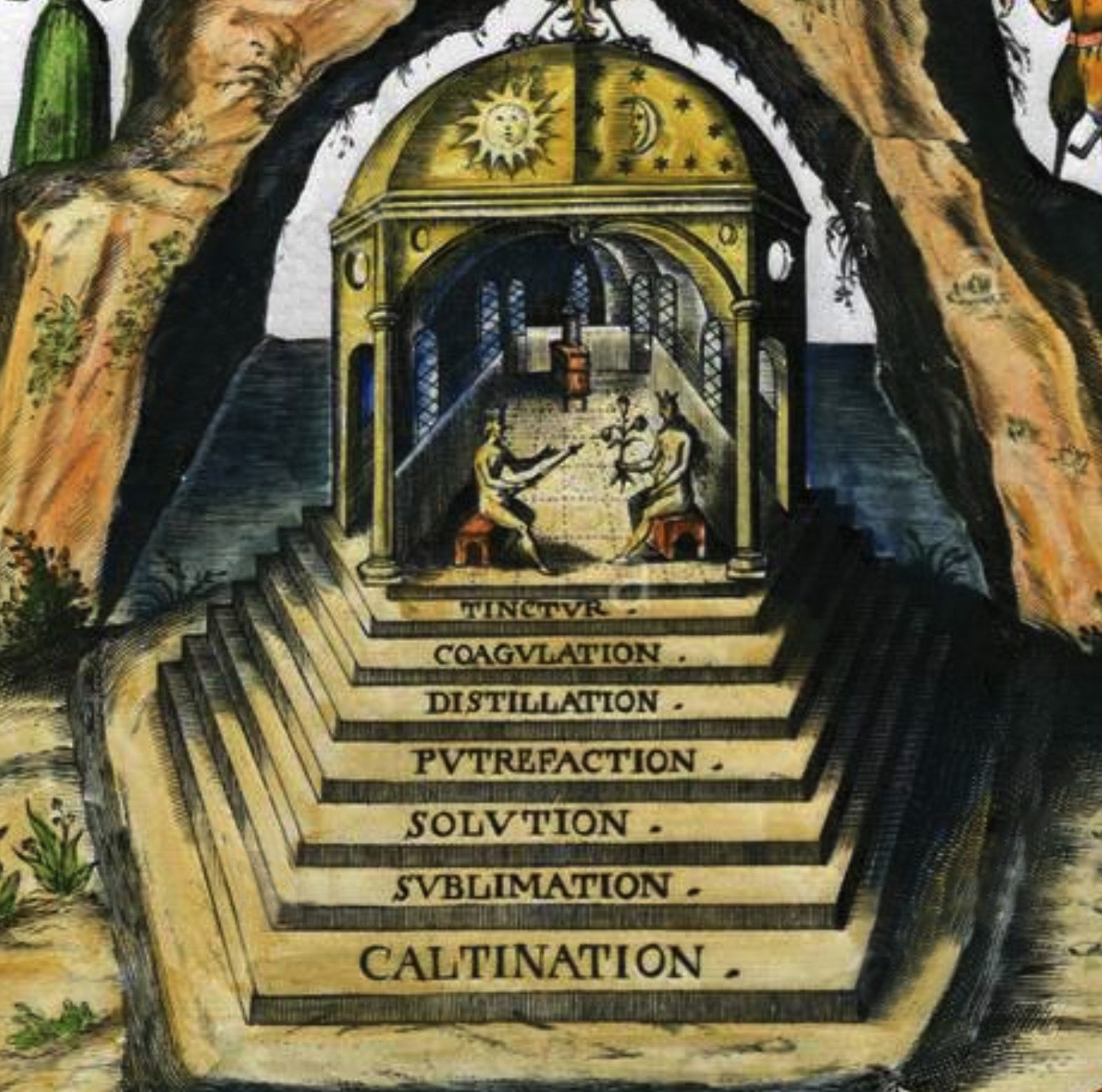

PRACTICAL ALCHEMY. FIELD TRANSMUTATIONS: 32 GANS MATRIX SCTUCTURES

MULTIPLE GANS MATRIX FORMATIONS

There are numerous Sambhogakāya realms

almost as numerous as deities in Tibetan Buddhism.

These Sambhogakaya-realms

are known as Buddha-fields or Pure

Lands.

In the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch,

Chan Master Huineng describes the Samboghakaya as a state in which the

practitioner continually and naturally produces good thoughts:

Think not of the past but of the future. Constantly maintain the future thoughts

to be good. This is what we call the Sambhogakāya.

Just one single evil thought could destroy the good karma that has continued for

one thousand years; and just one single good thought in turn could destroy the

evil karma that has lived for one thousand years.

If the future thoughts are always good, you may call this the Sambhogakāya. The

discriminative thinking arising from the Dharmakāya (法身↔fashen "Truth body") is

called the Nirmanakāya (化身↔huashen "transformation body"). The successive

thoughts that forever involve good are thus the Sambhogakāya.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Conscious presence.

Refuge Tree or Refuge Field paintings depict the important objects of "Refuge" for each sect or lineage in the form of a genealogical chart. Each lineage has its own distinctive form of composition but they usually include the "Three Jewels" (Sanskrit: triratna): Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, the "Refuges" common to all major schools of Buddhism. They may also include what is known in the Nyingma and Kagyu sects as the "Three Roots" (Tibetan: tsa sum) which include the numerous important Lamas and Lineage Holders, particular meditational deities (Tibetan: Yidam), the Dakinis (Tibetan: Khadroma) or the Protectors of the Lineage (Sanskrit: Dharmapāla, Tibetan: Chokyong). Many other figures such as Buddhist practitioners, animals, offering goddesses and other Buddhist symbols and imagery are also often included. A Refuge Tree painting may contain over a hundred figures, or only the key representative figures of each main grouping.

ONE

TWO

THREE

"LIFE RAYS EXPERIMENT"

Guess... just another transmutation and work on the fields of coherence...

Celestial manifestations

Sambhogakāya is a "subtle

body of limitless form". Buddhas such as Bhaisajyaguru and Amitābha, as well as

advanced bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteśvara and Manjusri can appear in an "enjoyment-body."

A Buddha can appear in an "enjoyment-body" to teach bodhisattvas through

visionary experiences.

Those Buddhas and Bodhisattvas manifest themselves in their specific pure lands.

These worlds are created for the benefits of others. In those lands it is easy

to hear and practice the Dharma. A person can be reborn in such a pure land by

"the transfer of some of the huge stock of 'merit' of a Land's presiding Buddha,

stimulated by devout prayer."

One of the places where

the Sambhogakāya appears is the extra-cosmic realm or pure land called Akaniṣṭha.

This realm should not be confused with the akanistha of the pure abodes, for it

is a realm that completely transcends it. Absolutely seen, only Dharmakāya is

real; Sambhogakāya and Nirmāṇakāya are "provisional ways of talking about and

apprehending it."

Understanding in Buddhist

tradition Tibetan Buddhism

There are numerous

Sambhogakāya realms almost as numerous as deities in Tibetan Buddhism. These

Sambhogakaya-realms are known as Buddha-fields or Pure Lands. One manifestation

of Sambhogakaya in Tibetan Buddhism is the rainbow body. This is where an

advanced practitioner is walled up in a cave or sewn inside a small yurt-like

tent shortly before death. For a period of a week or so after death, the

practitioners' body transforms into a Sambhogakaya (light body), leaving behind

only hair and nails.

Chán Buddhism

In the Chán (禪) (Jp. Zen) tradition, Sambhogakāya (Chin. 報身↔baoshen, lit. "retribution

body"), along with Dharmakaya and Nirmanakaya, are given metaphorical

interpretations. In the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, Chan Master

Huineng describes the Samboghakaya as a state in which the practitioner

continually and naturally produces good thoughts:

Think not of the past but

of the future. Constantly maintain the future thoughts to be good. This is what

we call the Sambhogakāya.

Just one single evil thought could destroy the good karma that has continued for

one thousand years; and just one single good thought in turn could destroy the

evil karma that has lived for one thousand years.

If the future thoughts are always good, you may call this the Sambhogakāya. The

discriminative thinking arising from the Dharmakāya (法身↔fashen "Truth body") is

called the Nirmanakāya (化身↔huashen "transformation body"). The successive

thoughts that forever involve good are thus the Sambhogakāya.

The Trikāya doctrine (Sanskrit:

"three bodies"; Chinese: 三身; pinyin: sānshēn; Japanese pronunciation: sanjin,

sanshin; Korean pronunciation: samsin; Vietnamese: tam thân, Tibetan: སྐུ་གསུམ,

Wylie: sku gsum) is a Mahayana Buddhist teaching on both the nature of reality

and the nature of Buddhahood. The doctrine says that Buddha has three kāyas or

bodies, the Dharmakāya (ultimate reality), the Saṃbhogakāya (divine incarnation

of Buddha), and the Nirmānakāya (physical incarnation of Buddha).

The doctrine says that a

Buddha has three kāyas or bodies:

The Dharmakāya, "Dharma body," ultimate reality, "pure being itself," Buddha

nature, emptiness, it is usually associated with Vairocana;

The Sambhogakāya, "Enjoyment (or Bliss) body," the divine Buddhas of the Buddha

realms, it is usually associated with Amitabha;

The Nirmānakāya, "Transformation (or Appearance) Body," physical appearance in

the world, it is usually associated with Gautama.

.jpg)

The Dharmakāya doctrine

was possibly first expounded in the Astasāhasrikā Prajńāpāramitā "The Perfection

of Wisdom In Eight Thousand Verses", composed in the 1st century BCE. Mahayana

Buddhism introduced the Sambhogakāya, which conceptually fits between the

Nirmāṇakāya (the manifestations of enlightenment in the physical world) and the

Dharmakaya. Around 300 CE, the Yogacara school systematized the prevalent ideas

on the nature of the Buddha in the Trikaya or three-body doctrine.

Various Buddhist traditions have different ideas about what the three bodies

are.

Chinese Buddhism

The Three Bodies of the Buddha consists of:

The Nirmaṇakāya, which is

a physical/manifest body of a Buddha. An example would be Gautama Buddha's body.

The Sambhogakāya, which is the reward/enjoyment body, whereby a bodhisattva

completes his vows and becomes a Buddha. Amitābha, Vajrasattva and Manjushri are

examples of Buddhas with the Sambhogakaya body.

The Dharmakāya, which is the embodiment of the truth itself, and it is commonly

seen as transcending the forms of physical and spiritual bodies. Vairocana

Buddha is often depicted as the Dharmakāya in the Chinese Esoteric Buddhist and

Huayan traditions.

As with earlier Buddhist thought, all three forms of the Buddha teach the same

Dharma, but take on different forms to expound the truth.

According to Schloegl, in the Zhenzhou Linji Huizhao Chansi Yulu (which is a

Chan Buddhist compilation), the Three Bodies of the Buddha are not taken as

absolute. They would be "mental configurations" that "are merely names or props"

and would only perform a role of light and shadow of the mind.

The Zhenzhou Linji Huizhao Chansi Yulu advises:

Do you wish to be not

different from the Buddhas and patriarchs? Then just do not look for anything

outside. The pure light of your own heart [i.e., 心, mind] at this instant is the

Dharmakaya Buddha in your own house. The non-differentiating light of your heart

at this instant is the Sambhogakaya Buddha in your own house. The

non-discriminating light of your own heart at this instant is the Nirmanakaya

Buddha in your own house. This trinity of the Buddha's body is none other than

here before your eyes, listening to my expounding the Dharma.

The Three Vajras, namely

"body, speech and mind", are a formulation within Vajrayana Buddhism and Bon

that hold the full experience of the śūnyatā "emptiness" of Buddha-nature, void

of all qualities (Wylie: yon tan) and marks (Wylie: mtshan dpe) and establish a

sound experiential key upon the continuum of the path to enlightenment. The

Three Vajras correspond to the trikaya and therefore also have correspondences

to the Three Roots and other refuge formulas of Tibetan Buddhism. The Three

Vajras are viewed in twilight language as a form of the Three Jewels, which

imply purity of action, speech and thought.

The Three Vajras are often

mentioned in Vajrayana discourse, particularly in relation to samaya, the vows

undertaken between a practitioner and their guru during empowerment. The term is

also used during Anuttarayoga Tantra practice.

The Three Vajras are often employed in tantric sādhanā at various stages during

the visualization of the generation stage, refuge tree, guru yoga and istadevatā

processes. The concept of the Three Vajras serves in the twilight language to

convey polysemic meanings, aiding the practitioner to conflate and unify the

mindstream of the istadevatā, the guru and the sādhaka in order for the

practitioner to experience their own Buddha-nature.

Speaking for the Nyingma

tradition, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche perceives an identity and relationship between

Buddha-nature, dharmadhatu, dharmakāya, rigpa and the Three Vajras:

Dharmadhātu is adorned

with Dharmakāya, which is endowed with Dharmadhātu Wisdom. This is a brief but

very profound statement, because "Dharmadhātu" also refers to Sugatagarbha or

Buddha-Nature. Buddha- Nature is all-encompassing... This Buddha-Nature is

present just as the shining sun is present in the sky. It is indivisible from

the Three Vajras [i.e. the Buddha's Body, Speech and Mind] of the awakened

state, which do not perish or change.

The trinity of body,

speech, and mind are known as the three gates, three receptacles or three vajras,

and correspond to the western religious concept of righteous thought (mind),

word (speech), and deed (body). The three vajras also correspond to the three

kayas, with the aspect of body located at the crown (nirmanakaya), the aspect of

speech at the throat (sambhogakaya), and the aspect of mind at the heart (dharmakaya)."

The bīja corresponding to

the Three Vajras are: a white om (enlightened body), a red ah (enlightened

speech) and a blue hum (enlightened mind).

Simmer-Brown asserts that:

When informed by tantric views of embodiment, the physical body is understood as

a sacred mandala (Wylie: lus kyi dkyil).

This explicates the semiotic rationale for the nomenclature of the somatic

discipline called trul khor. Barron et al., renders from Tibetan into English, a

terma "pure vision" (Wylie: dag snang) of Sri Singha by Dudjom Lingpa that

describes the Dzogchen state of 'formal meditative equipoise' (Tibetan: nyam-par

zhag-pa) which is the indivisible fulfillment of vipaśyanā and śamatha, Sri

Singha states:

Just as water, which

exists in a naturally free-flowing state, freezes into ice under the influence

of a cold wind, so the ground of being exists in a naturally free state, with

the entire spectrum of samsara established solely by the influence of perceiving

in terms of identity.

Understanding this

fundamental nature, you give up the three kinds of physical activity--good, bad,

and neutral--and sit like a corpse in a charnal ground, with nothing needing to

be done. You likewise give up the three kinds of verbal activity, remaining like

a mute, as well as the three kinds of mental activity, resting without

contrivance like the autumn sky free of the three polluting conditions.

Vajrayana sometimes refers

to a fourth body called the svābhāvikakāya (Tibetan: ངོ་བོ་ཉིད་ཀྱི་སྐུ, Wylie:

ngo bo nyid kyi sku) "essential body", and to a fifth body, called the

mahāsūkhakāya (Wylie: bde ba chen po'i sku, "great bliss body"). The

svābhāvikakāya is simply the unity or non-separateness of the three kayas. The

term is also known in Gelug teachings, where it is one of the assumed two

aspects of the dharmakāya: svābhāvikakāya "essence body" and jńānakāya "body of

wisdom". Haribhadra claims that the Abhisamayalankara describes Buddhahood

through four kāyas in chapter 8: svābhāvikakāya, [jńāna]dharmakāya, sambhogakāya

and nirmāṇakāya.

In dzogchen teachings, "dharmakaya"

means the buddha-nature's absence of self-nature, that is, its emptiness of a

conceptualizable essence, its cognizance or clarity is the sambhogakaya, and the

fact that its capacity is 'suffused with self-existing awareness' is the

nirmanakaya.

The interpretation in Mahamudra is similar: When the mahamudra practices come to

fruition, one sees that the mind and all phenomena are fundamentally empty of

any identity; this emptiness is called dharmakāya. One perceives that the

essence of mind is empty, but that it also has a potentiality that takes the

form of luminosity. In Mahamudra thought, Sambhogakāya is understood to be this

luminosity. Nirmanakāya is understood to be the powerful force with which the

potentiality affects living beings.

In the view of Anuyoga,

the Mind Stream (Sanskrit: citta santana) is the 'continuity' (Sanskrit: santana;

Wylie: rgyud) that links the Trikaya. The Trikāya, as a triune, is symbolised by

the Gankyil.

A ḍākinī (Tibetan: མཁའ་འགྲོ་[མ་], Wylie: mkha' 'gro [ma] khandro[ma]) is a

tantric deity described as a female embodiment of enlightened energy. The

Sanskrit term is likely related to the term for drumming, while the Tibetan term

means "sky goer" and may have originated in the Sanskrit khecara, a term from

the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra.

Dākinīs can also be

classified according to the trikāya theory. The dharmakāya Dākinī, which is

Samantabhadrī, represents the dharmadhatu where all phenomena appear. The

sambhogakāya Dākinī are the yidams used as meditational deities for tantric

practice. The nirmanakaya Dākinīs are human women born with special

potentialities; these are realized yogini, the consorts of the gurus, or even

all women in general as they may be classified into the families of the Five

Tathagatas.

Leela attitude (Thai: ปางลีลา;

RTGS: pang lila) is an attitude of Buddha in Thai art of which the Buddha is

stepping with his right foot and his right hand swinging and the other hand put

towards to the front. The attitude is sometimes called the Walking Buddha. The

attitude refers to the episode where he is walking back to the earth from Dao

Wadeung heaven (Trayastrimsa/Tavatimsa) with Devas and Brahmas that follow.

Leela

Way in, Way out... Quantum Leap

Instrumental Metaphysics

Hello there

The Astasāhasrikā Prajńāpāramitā

Sūtra; English: The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand [Lines]) is a

Mahāyāna Buddhist sūtra in the category of Prajńāpāramitā sūtra literature. The

sūtra's manuscript witnesses date to at least ca. 50 CE, making it among the

oldest Buddhist manuscripts in existence.

The sūtra forms the basis for the expansion and development of the

Prajńāpāramitā sūtra literature. In terms of its influence in the development of

Buddhist philosophical thought, P.L. Vaidya writes that "all Buddhist writers

from Nāgārjuna, Āryadeva, Maitreyanātha, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Dignāga, down to

Haribhadra concentrated their energies in interpreting Astasāhasrikā only,"

making it of great significance in the development of Madhyāmaka and Yogācāra

thought.

The sūtra deals with a number of topics, but is primarily concerned with the

conduct of a bodhisattva, the realisation and attainment of the Perfection of

Wisdom as one of the Six Perfections, the realisation of thusness (tathātā), the

attainment of irreversibility on the path to buddhahood (avaivartika),

non-conceptualisation and abandonment of views, as well as the worldly and

spiritual benefit of worshipping the sūtra.

Title

The Sanskrit title for the sūtra, Astasāhasrikā Prajńāpāramitā Sūtram, literally

translates as "The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Sūtra." The "Eight

Thousand," Edward Conze indicates, refers roughly to ślokas, which have a count

of thirty two syllables. Regarding this, Conze writes, "The Cambridge manuscript

Add 866 of A.D. 1008 gives the actual number of slokas after each chapter, and

added together they are exactly 8,411." This title is likely late in origin, as

Seishi Karashima writes regarding the text from which Lokakṣema (fl. 147–189)

was translating, the text was probably originally just entitled Prajńāpāramitā

or Mahāprajńāpāramitā. But when different versions began circulating, the

additional titles, such as references to length, were added in order to

differentiate them. The name of Lokakṣema's translation thus became Dŕohéng

Bānruňbōluómě Jīng, "The Way of Practice Perfection of Wisdom Sūtra," with the

extra element "Dŕohéng" taken from the name of the first chapter.

The sūtra is among the most well-established in the Mahāyāna tradition and "was

the first philosophical text to be translated from the Mahāyāna literature into

Chinese." It was translated seven times into Chinese, five times into Tibetan,

and eight times into Mongolian. Its titles in the languages of these various

countries include:

Astasāhasrikā-prajńāpāramitā-sūtram, "The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand

[Lines]."

Chinese:

道行般若波羅蜜經, Dŕohéng Bānruňbōluómě Jīng, "The Way of Practice Prajńāpāramitā Sūtra."

T224 (Trans. Lokakṣema, 179 CE )

大明度經, Dŕmíngdů Jīng, "The Great Prajńāpāramitā Sūtra." T225 (Trans. Zhī Qīan &

Kāng Sēnghůi, 223-229 CE)[12]

般若鈔經, Bānruň Chāo Jīng, "The Small Prajńā Sūtra." T226 (Trans. Dharmarakṣa, 386

CE)

小品般若波羅蜜經, Xiaŏpĭn Bānruňbōluómě Jīng, "The Small Section Prajńāpāramitā Sūtra."

T227 (Trans. Kumārajīva, 408 CE)

Assembly 4 of 大般若波羅蜜多經, Dŕbānruňbōluóměduō Jīng, "The Great Prajńāpāramitā Sūtra."

T220 fasc. 538–555 (Trans. Xuánzŕng, 660 CE)

Assembly 5 of 大般若波羅蜜多經, Dŕbānruňbōluóměduō Jīng, "The Great Prajńāpāramitā Sūtra."

T220 fasc. 556–565 (Trans. Xuánzŕng, 660 CE) — Both of Xuánzŕng's translations

are equivalent to the Aṣṭasāhasrikā with the exception of his exclusion of the

Sadāprarudita story.

佛母出生三法藏般若波羅蜜多經, Fómŭ Chūshēng Sānfăzŕng Bānruňbōluóměduō Jīng, "The Three Dharma

Treasuries for the Attainment of Buddhahood Prajńāpāramitā Sūtra." T228 (Trans.

Dānapāla, 1004 CE)

Japanese: 八千頌般若経 (はっせんじゅはんにゃきょう), Hassenju Hannya Kyō, "The Eight Thousand [Line]

Prajńā Sūtra." This term refers to the Sanskrit source text, rather than the

Chinese translations which are prevalent in Japanese Buddhist usage.

Tibetan: ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པ་ བརྒྱད་སྟོང་པ་, Shes-rab-kyi pha-rol-tu

phyin-pa brgyad stong-pa, "The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines."

(Trans. Ye-shes-sde, 9th C.)

Mongolian: Naĭman mi͡angat Ikh Khȯlgȯn sudar orshivoĭ, "The Perfection of Wisdom

in Eight Thousand Lines."

History

Indian Developments

Traditional Theories of Formation

While it is held by some in the Mahāyāna tradition that the Buddha taught the

Aṣṭasāhasrikā, and the other Mahāyāna sūtras during his lifetime, some legends

exist regarding its appearance in the world after the Buddha's parinirvāṇa. One

such legend is that Mańjuśrī Bodhisattva came to the house of King Candragupta

(321–297 BCE), preached, and left the Aṣṭasāhasrikā there. Another, related by

Haribhadra (8th C), is that while the Śrāvakayāna teachings were entrusted and

preserved by Ānanda, the Mahāyāna sūtras, and in particular the "Prajńāpāramitā

Sūtra," were entrusted to Vajradhāra residing in the Aḍakavatī Heaven. Finally,

the legend which has the most currency in East Asia, is that Nāgārjuna was

gifted the sūtra from the king of the nāgas after seeing Nāgārjuna's resolve to

obtain the Mahāyāna sūtras of the Buddha that were missing on earth.

It is clear that Indian monastics did not see the development of the

Prajńāpāramitā literature in the first millennium as an outgrowth from the

Aṣṭasāhasrikā, an early opinion, but Dignāga (c. 480–540 CE), suggests "we

assert that this Eight Thousand is a condensed version [of the Perfection of

Wisdom] text, not short of any of the topics. It proclaims the very same topics

that the longer sūtras] have proclaimed." Later, Haribhadra suggests that the

Buddha "demonstrated the [Śatasāhasrikā] to bring benefit to those beings who

are devoted to words and delight in extensively worked-out rendition,

demonstrated the [Pańcaviṃśatisāhasrikā], through gathering all the topics

together, out of affection for those beings who delight in middle-sized [renditions]

and understand from selective elaboration, and taught the [Astasāhasrikā],

through condensing its topics, to produce benefit for beings who are captured by

headings and delight in brief explanation." Haribhadra, however, uses the topics

of the Pańcaviṃśatisāhasrikā, which were the basis of the Abhisamayālaṅkāra of

Asaṅga (4th C) on which his commentary relies, in order to explain the

Astasāhasrikā.

Chinese monastics in general also held that the translations corresponding to

the Astasāhasrikā were redacted from the medium sūtras (e.g. translations of the

Pańcaviṃśatisāhasrikā)—despite the fact that large portions of the shorter

versions of the sūtra are absent from the larger texts. For instance, Dŕo’ān

(312-385 CE) theorised that Indian monks redacted the Dŕohéng translation from

the longer sūtras, but also that the longer sūtras could be used as commentaries

on the Dŕohéng. Similarly, Zhī Dŕolín (314-366 CE) suggested that monks had

redacted the Xiăopĭn translation from the medium sūtra.

Contemporary Theories on Formation

Contemporary scholarship holds that the shorter Prajńāpāramitā sūtras, using the

Astasāhasrikā as the base, were redacted and expanded in the formation of the

longer sūtras. As Jan Nattier characterises,

the evolution of the Astasāhasrikā-Prajńāpāramitā into the

Pańcaviṃsati-sāhasrikā through what we might call the “club sandwich” style of

textual formation: with the exception of the final chapters (30-32 in the

Sanskrit version) of the Asta-, which have no counterpart in the Sanskrit Pańca-

and apparently circulated separately before being incorporated into the Asta-

... the [Pańca-] consists of the Aṣṭa- being “sliced” like a loaf of bread and

then layered with “fillings” introduced from other sources. Very little of the

text of the Asta- has been altered in the process, and only rarely does a crumb

of the “bread” seem to have dropped out. The Pańca- is not simply related to the

Asta-; it is the Asta-, with the addition of a number of layers of new material.

Similarly, Edward Conze suggested a nine-stage model of expansion. (1) A base

urtext of the Ratnagunasaṃcaya Gāthā, starting with the first two chapters. (2)

Chapters 3 to 28 of the Ratnagunasaṃcaya were added, which were then put into

prose as the Astasāhasrikā. To this were gradually added (3) material from the

Abhidharma, (4) concessions to the "Buddhism of Faith" (referring to Pure Land

references in the sūtra), and then (5) the expansion into the larger sūtras,

their (6) contraction into the shorter sūtras (i.e. Diamond Sūtra, Heart Sūtra,

down to the Prajńāpāramitā in One Letter), which all in turn set the basis for

the (7) Yogācārin commentaries and (8) Tantras and (9) Chan.

Based on a similar understanding, most scholars of the Prajńāpāramitā have

suggested that there is a base urtext from which the rest of the Astasāhasrikā

expanded. Similar to Conze in regards to the Ratnagunasaṃcaya, scholars who hold

that the first chapter of the prose sūtra is the urtext include Kōun Kajiyoshi,

Yěnshůn, and Lambert Schmithausen. Ryūshō Hikata argued that the sūtra was

composed in two phases from Chapter 1 to 25, but that material from Chapter 26

to 32 and references to Akṣobhya were later developments. P.L. Vaidya is alone

in suggesting that the urtext is "Dharmodgata's sermon to Sadāprarudita" at

Chapter 31.

Matthew Orsborn presents a dissenting opinion to the urtext theories, holding

that the presence of chiastic structures may point "to the entire sūtra being

composed as a single and unified whole as it presently stands (more or less),"

with additional materials being added around these chiastically arranged

materials.

Commentarial Tradition

The primary subject of Prajńāpāramitā commentary has been the

Pańcaviṃśatisāhasrikā version. This includes the commentaries attributed to

Nāgārjuna, Dignāga, and Asaṅga's Abhisamayālaṅkāra. Using the Abhisamayālaṅkāra

as a basis, however, Haribhadra composed a commentary on the Aṣṭasāhasrikā, the

Abhisamayālaṅkārāloka, or the "Light for the Ornament of Clear Realisation."

While, owing to it being based on a commentary on a different text, the

structure suggested to be present by Haribhadra does not fit perfectly, the

structure as he understands it is as follows:

The Three Knowledges

Knowledge of all Aspects Chapter 1

Knowledge of all Paths Chapters 2-7

All-Knowledge Chapter 8

The Four Practices

Full Awakening to All Aspects Chapters 9-19

Culmination Realisation Chapters 20-28

Serial Realisation Chapter 29

Instant Realisation Chapter 29

The Dharma Body

Full Awakening to the Dharma Body Chapters 30-32

Manuscripts and Editions

Aṣṭasāhasrikā manuscript. Cleveland Museum of Art.

The following is a chronological survey of prominent manuscript witnesses and

editions of the Sanskrit Aṣṭasāhasrikā text:

c. 50 CE — Kharoṣṭhī manuscript from the Split Collection. This is in the

Gāndhārī language and was composed in Gandhāra.

c. 140 CE — Kharoṣṭhī manuscript from the Bajaur Collection. This manuscript is

also in the Gāndhārī language and was composed in Gandhāra.

c. 200 CE — Fragments in late Kuṣāṇa Brāhmī from Anonymous - Perfection of

Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines, Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita, Decorated Leaf -

1938.301.5 - Cleveland Museum of Art.tiffhe Schřyen collection. This manuscript

is in Sanskrit but was probably also composed in Gandhāra.

975 CE — Cambridge MS Add. 1464. Composed in Bengal.

c. 1000 CE — Cambridge MS Add. 1163. Composed in Nepal.

1008 CE — Cambridge MS Add. 866. Composed in Nepal.

1015 CE — Cambridge MS Add. 1643. Composed in Kathmandu, Nepal.

1264 CE — Cambridge MS Add. 1465. Composed in Nepal.

Three other Cambridge manuscripts exist.

The Nepalese-German Manuscript Cataloguing Project lists 97 Aṣṭasāhasrikā

manuscripts in archives.

The following editions have been made of the Sanskrit text:

1888 — ed. Rajendra Lal Mitra. This edition is in Devanāgarī and was prepared

using:

a Bengali transcript of a 19th-century Nepalese original

a Nepalese manuscript provided by Brian Houghton Hodgson dating to 1061

a Nālandā manuscript from the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain dating to

12th century

a Nālandā manuscript from the Asiatic Society of Bengal dating to 1097

Two manuscripts from Nepal, which Mitra judged to be older than the previous

manuscript

a 12th-century manuscript of Nepalese origin

1932-5 — ed. Unrai Wogihara. This edition corrects many of Mitra's errata, and

also features the running commentary of Haribhadra using manuscripts of the

Abhisamayālaṅkārāloka loaned from Sylvain Lévi and the Calcutta Library.

1960 — ed. Paraśurāma Lakṣmaṇa Vaidya. This edition is based on Wogihara and

Mitra, and attempts to correct perceived errors in sandhi.

Translations into Western Languages

The Aṣṭasāhasrikā first became known to western scholars when Brian Hodgson had

obtained manuscripts of the sūtra in Nepal and sent them to the Indologist

Eugčne Burnouf (1801-1852) in Paris for analysis. Burnouf's first impression was

lack of interest, "because I saw only perpetual repetitions of the advantages

and merits promised to those who obtain prajńāpāramitā. But what is this prajńā

itself? This is what I did not see anywhere, and what I wished to learn." Later,

in his 1844 work on the history of Indian Buddhism, Burnouf presented the first

detailed study of the doctrines of the Prajńāpāramitā found in the west. In that

work, he also produced a translation of the first chapter and stated "I have

translated, for my personal use, almost all of the Prajńā in eight thousand

articles". This French translation was published in 2022 by Guillaume Ducoeur (Aṣṭasāhasrikā

Prajńāpāramitā, la Perfection de sagesse en huit mille stances, traduite par

Eugčne Burnouf (1801-1852), éditée par Guillaume Ducoeur, Université de

Strasbourg, 2022) .

The only full published translation remains Edward Conze's 1973 translation, The

Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines and its Verse Summary. A

translation of the first two chapters of Kumārajīva's version was published by

Matt Orsborn (=Shi Huifeng) in 2018.

Outline

The structure of the sūtra can be understood in a number of ways. But four clear

divisions can be noted:

Chapters 1–2: These chapters, besides setting the stage and introducing the

themes of the sūtra by defining bodhisattvas and mahāsattvas, are also

considered to be the urtext by a number of scholars.

Chapters 3–16: These chapters, according to Orsborn, expand upon the theme of

the bodhisattvas' approach to understanding the Prajńāpāramitā and the benefits

of the sūtra, and culminate in the bodhisattva's realisation of tathatā. This

marks Chapter 16 as the central turning point in the sūtra and the centre of its

chiastic structure.

Chapters 17–29: These chapters continue to expand upon the same themes, but this

time the subject as bodhisattva is characterised as irreversible on the path to

buddhahood. The approach to the Prajńāpāramitā in this half can be understood as

that of one who has realised tathatā.

Chapters 30–32: These chapters mark a distinct break, in that they relate the

past example of the bodhisattva Sadāprarudita who seeks the Prajńāpāramitā from

the teacher Dharmodgata. The sūtra is concluded with an entrustment to Ānanda.

Chapters 1-2: Introduction

Chapter 1: The Practice of the Knowledge of all Modes — While at Vulture Peak,

the Buddha asks Subhūti to explain how bodhisattvas realise the Prajńāpāramitā.

Subhūti explains that when disciples of the Buddha who realise dharmatā teach,

that is the work of the Buddha. He goes on to clarify the realisation of the

Perfection of Wisdom by explaining that by cutting off the view of the inherent

existence of self and phenomena, a bodhisattva can go forth on the Mahāyāna for

the liberation of beings and not enter nirvāṇa halfway. However, in suchness, he

points out, there are in fact no bodhisattvas, beings to save, Prajńāpāramitā,

path, or nirvāṇa.

Śakra.

Chapter 2: Śakra — In response to Śakra's request for further explanation,

Subhūti points out that in suchness one cannot rely on any aggregate, state of

being, or the path, all of which are illusions. All, including the

Prajńāpāramitā, are said to be without beginning, middle, or end, and therefore

are infinite. The devas declare that they will highly regard a bodhisattva who

practices as Subhūti describes—the Buddha relates how he was such a bodhisattva

in the past when he met Dīpankara Buddha.

Chapters 3-16: The Bodhisattva's Training in the Prajńāpāramitā

Chapter 3. Reverence for the Receptacle of the Perfections, which holds

Immeasurable Good Qualities — This chapter emphasises the worldly benefits of

practicing the Prajńāpāramitā and writing it as a book and worshipping it. The

devas also declare that they will come and gather around one who does this. This

chapter also points out that the Prajńāpāramitā is the root of the other of the

Six Pāramitās. Worshipping the Prajńāpāramitā as a book is said to be superior

to worshipping stūpas because it is the source of buddhas themselves.

Chapter 4. The Proclamation of Qualities — Śakra points out that the

Prajńāpāramitā is the source of all buddhas, thus in worshipping buddha relics

one is really worshipping the Prajńāpāramitā. Prajńāpāramitā, also, ultimately

contains the other five pāramitās—so practicing it allows one to practice the

others.

Chapter 5. The Revolution of Merit — Practicing the Prajńāpāramitā is said to be

of great merit, but teaching it to others is said to be even greater. However,

if it is taught in the form of annihilationist doctrine, it is called the "counterfeit

Prajńāpāramitā." Finally, it is declared to be the greatest gift since it

renders full buddhahood.

Chapter 6. Dedication and jubilation — The chapter points out that one should

rejoice in the merit of others and one's own practice and dedicate it to

attaining buddhahood, but without perceiving any sign in doing so.

Naraka: Buddhist hell

Chapter 7. Hell — While the Prajńāpāramitā should be considered the teacher, it

is not to be thought of as procuring anything and should be practiced through

non-practice: this leads beings to nirvāṇa but does not result in perceiving

beings or nirvāṇa. If one obtains the sūtra, it is said to be because one

encountered the buddhas previously, but that it is understood depending upon

one's conditions. If, however, one rejects the Prajńāpāramitā, hell is said to

be the retribution.

Chapter 8. Purity – This chapter points out that ultimately the skandhas are

pure, and so is the Prajńāpāramitā. Seeing this one is non-attached, but not

seeing it, one develops attachment. Teaching and not teaching the Prajńāpāramitā

and the skandhas is said to have no effect upon their increase or decrease,

since they are ultimately like space. The Buddha points out that just as he

teaches, so did all past buddhas, and so will Maitreya in the future.

Chapter 9. Praise — The Prajńāpāramitā is declared to be just a name which is

not produced, stopped, defiled, or pure. Beings who hear it will be free from

suffering, but some people will be hostile to its spread. Nonetheless, it is

said to be pure and neither proceeds nor recedes due to its unproduced and

isolated nature.

Chapter 10. Proclamation of the Qualities of Bearing in Mind — This chapter

emphasises how people who practice the Prajńāpāramitā have planted karmic roots

with past buddhas. If one encounters it and is not afraid, one is said to be

near to realising the Prajńāpāramitā, and one develops one's practice in this

regard by not mentally constructing the path. While Māra will try to obstruct

such bodhisattvas, they will be sustained by the buddhas. It is said that the

sūtra will spread long after the Buddha's nirvāṇa and that those who search for

it will find it in one to two lives.

Depictions of Māra's demons from an Aṣṭasāhasrikā manuscript.

Chapter 11. Māra's Deeds — This chapter returns to the topic of Māra by pointing

out how he will try to dissuade bodhisattvas from the Prajńāpāramitā. He does

this in particular by making bodhisattvas slothful, creating obstacles between

the student and his teacher, making them feel like the Śrāvakayāna sūtras are of

greater value, and manifesting as people, such as an illusory buddha, who will

give rise to doubts through misleading teachings.

Chapter 12. Showing the World — This chapter emphasises how the Prajńāpāramitā

is the mother of the buddhas: therefore they care for her, just as a child for

his mother, by teaching the Prajńāpāramitā. The world to which it is taught is

declared to be made up of empty skandhas, and thus the world, too, is said to be

empty. Similarly all beings' thoughts are characterised by emptiness, are

identical to suchness, and are inherently pure. One cannot fix onto any

phenomenon, just like space, and are ultimately unknowable—viewing them thus

through non-viewing is said to be viewing the world.

Chapter 13. Unthinkable — The Prajńāpāramitā is said to be unthinkable and

incalculable like space. The same is so of all skandhas, phenomena, attainments.

All of the levels of the path are said to work through the agency of the

Prajńāpāramitā as a minister does a king's work. The Prajńāpāramitā is

summarised as being the non-attachment to any phenomena. It is said to be heard

due to one's karmic roots, and accepting it is said to accelerate one's progress

on the path.

Chapter 14. Similes — This chapter points out that practitioners of the

Prajńāpāramitā may have been born in a buddha-field in a previous life, but that

generally they will be born as humans. If one fails to understand the

Prajńāpāramitā, it may have been due to failing to question buddhas about it in

the past. Moreover, the chapter suggests that if a bodhisattva does not rely

upon the Prajńāpāramitā and skilful means, they may backslide to the śrāvakayāna

or pratyekabuddhayāna.

Chapter 15. Gods — This chapter suggests that bodhisattva training relies upon

good friends who point out the Prajńāpāramitā. These are equated to bodhisattvas

who abide in signless suchness, and who do not tremble in encountering the

Prajńāpāramitā. It suggests that the bodhisattva aspiration is not related to

phenomena, and that the non-grasping nature of the Dharma is demonstrated

through non-demonstration.

Chapter 16. Suchness — This chapter, being the turning point in terms of

identifying the end of retrogression in the realisation of suchness, emphasises

that the Buddha, suchness, and phenomena are identical and non-dual—to know this

is said to be buddhahood. Those who have backslided, as suggested in Chapter 14,

must rely upon the Prajńāpāramitā in order to once again enter the buddhayāna.

In that regard, the difficulty of buddhahood is said to be that there is no one

to attain it, and no three yānas by which to approach it—awakening is knowing

this without trembling.

Chapters 17-29: The Irreversible Bodhisattva's Training in the Prajńāpāramitaa

Chapter 17. Attributes, Tokens, and Signs of Irreversibility — Having attained

irreversibility, a bodhisattva has no doubt of his irreversibility. Without

doubt, their conduct is pure and continue to work for beings' benefit. They

cannot be dissuaded by Māra, who will be easily recognised by them.

Chapter 18. Emptiness — Bodhisattva stages are equated with suchness. Reflecting

upon them, a bodhisattva develops the Prajńāpāramitā. The greatest of deeds is

excelled by practicing the Prajńāpāramitā for even a single day. Awakening never

increases or decreases to such a bodhisattva, whose activities and merits are

said to be ineffable.

Akṣobhya Buddha

Chapter 19. The Goddess of the Ganges — Awakening is said to arise depending

upon the first and last bodhicitta aspiration, but not directly by either. In

suchness, development to awakening is said to only be a convention. Objective

bases are said to be that upon which discriminative actions depend, but they are

said to be empty. Moreover, conditionality is said to only exist by convention

of speech, but not in reality. Practicing thus without fear, a bodhisattva

should endure misfortunes and dedicate them to awakening.

The Goddess of the Ganges gains faith in the Prajńāpāramitā and it is predicted

that after she studies under the Buddha Akṣobhya, she will become a Buddha

called Suvarṇapuṣpa.

Chapter 20. Discussion of Skill in Means — This chapter describes how a

bodhisattva can engage in skilful means by remaining in the world and not

entering nirvāṇa in order to benefit beings. They do this by holding back from

realising the reality-limit. They continue by developing the pāramitās and

engaging in non-attachment. They can know their own irreversibility when they

see signs in their dreams, and develop powers.

Chapter 21. Māra's Deeds — Returning to the topic of Māra, this chapter points

out how Māra may give rise to conceit in bodhisattvas by making them mistakenly

think they attained powers, or implanting false memories of past lives as monks,

or predictions to buddhahood. Becoming conceited, the bodhisattvas will renounce

the Prajńāpāramitā and return to the śrāvakayāna or pratyekabuddhayāna.

Similarly, bodhisattvas living in isolation are said to be particularly targeted

by Māra, who will give rise to their arrogance against city-dwelling

bodhisattvas. It is emphasised that these can be counteracted by honouring the

good friends.

Chapter 22. The Good Friends — The true good friends are declared to be the Six

Pāramitās, with Prajńāpāramitā as their key. Relying upon it, a bodhisattva sees

all as empty and pure. Thus, the Prajńāpāramitā is equated to a precious jewel.

Also, in this way, beings and the Prajńāpāramitā are said to neither increase or

decrease, and by not practicing in anything one practices in the Prajńāpāramitā.

Chapter 23. Śakra — It is said that by practicing and teaching the

Prajńāpāramitā, all devas are surpassed by a bodhisattva. The devas will

therefore protect that bodhisattva—but they can only accomplish this through the

Buddha's power.

Chapter 24. Conceit — If, however, a bodhisattva does not practice the

Prajńāpāramitā properly, they will be open to Māra who will give rise to their

conceit. However, by practicing repentance, a bodhisattva can avoid malice and

regard all bodhisattvas as their teacher and avoid competitive-mindedness.

Chapter 25. Training — To train in omniscience, a bodhisattva trains in suchness,

without grasping onto either. It is also suggested in this chapter that the

number of bodhisattvas who truly train in the Prajńāpāramitā are very few in

number, but that the merit of practicing the Prajńāpāramitā is greater than any

other practice. Bodhisattvas are thus able to teach śrāvakas by learning about

their qualities, but do not fall to their yāna.

Chapter 26. Like Illusion — While bodhisattvas surpass all except buddhas, and

the merits of their bodhicitta is said to be boundless, they are an illusion,

and thus cannot know the illusion that is also full awakening. Their bodhicitta,

too, is an illusion. Thus, they act conventionally in the world as puppets—knowing

that this is hard to do, while there is no one to do it and nothing to do.

Chapter 27. The Core — In this way, bodhisattva practice is insubstantial, but

they do not lose motivation because there is nothing that is there to lose

motivation. Bodhisattvas practicing in this way are protected by devas, and

praised by buddhas and bodhisattvas from other worlds.

Chapter 28. Avakīrṇakusuma — The Buddha declares that all the monks in the

assembly will become buddhas called Avakīrṇakusuma. The Buddha then entrusts the

sūtra to Ānanda for the first time, declaring that it should be worshipped. The

Buddha makes a vision of Akṣobhya's buddha-field arise and cease, and says that

just as it arises and ceases, one should not train in a fixed idea. In this way,

the Prajńāpāramitā is declared to be boundless, and thus its form in book form

is not really the Prajńāpāramitā. Finally it is said that the Prajńāpāramitā is

consummated through seeing non-extinction of the skandhas and seeing the links

of dependent origination.

Chapter 29. Approaches — The approach to the Prajńāpāramitā is said to be

through non-conceptualisation in 54 aspects. The declarations of the

Prajńāpāramitā are to be approached through the "roaring of a lion," but one

should also know that the qualities of the skandhas are equal to those of the

Prajńāpāramitā. Bodhisattvas who practice with this understanding are said to

find it easy to become a buddha.

Chapters 30-32: Sadāprarudita and Conclusion

A 1307 Korean painting depicting Sadāprarudita rising in the air after learning

from Dharmodgata.

Chapter 30. Sadāprarudita — The Buddha teaches Subhūti that one should seek the

Prajńāpāramitā just like the Bodhisattva Sadāprarudita ("Always Weeping"). In

relating his story, the Buddha explains that Sadāprarudita, who seeks the

Prajńāpāramitā, is told to go east by a voice, and then told by visions of the

buddhas to seek the teacher Dharmodgata in Gandhavatī. Sadāprarudita's desire at

that point is to know from whence the buddhas came and to where they went. Not

having anything to offer the teacher as payment, Sadāprarudita offers himself

for payment, but Māra deafens everyone so that they cannot hear him. Knowing

this, Śakra manifests as a brahmin who offers to buy Sadāprarudita's heart,

blood, and marrow. Agreeing and dissecting himself, he is saved by a merchant's

daughter who offers to help him with her riches. Seeing his resolve, Śakra

restores Sadāprarudita's dissected body parts and magically disappears. After

finding Dharmodgata and honouring him, Sadāprarudita asks him from whence the

buddhas came and to where they went.

Chapter 31. Dharmodgata — In response, Dharmodgata suggests that the buddhas

neither come nor go, since they are suchness. Sadāprarudita, rising in the air,

offers himself to Dharmodgata. The merchant's daughter does likewise.

Dharmodgata enters a samādhi for seven years—during this time, Sadāprarudita and

the merchant's daughter stand outside his house for seven years. After leaving

his samādhi, Dharmodgata teaches them the Prajńāpāramitā. Following this,

Sadāprarudita enters millions of samādhis, including that of the "sameness of

all phenomena."

Chapter 32. Entrusting — The Buddha concludes by saying that Sadāprarudita, from

then on, was never deprived of vision of the buddhas.

After this, the Buddha again entrusts the sūtra to Ānanda, instructing him to

copy and worship it as a book. He declares that so long as the Prajńāpāramitā

exists, so long does the Buddha continue to teach the Dharma

Jedi Path Metaphysical and

Alchemical Works

Written and compiled by Jedi Simon for educationl

purpose.2023 All rights reserved.

Addendum

A poetic conversion by Salomeea

Romanescu

From elements five, we're

made,

Earth, water, fire, air, and space.

High vibrations, slowing fade,

To form the building blocks of our place.

In Dzogchen's view, the cosmos is clear,

Open, translucent, and utterly free.

From air, wind moves with vigor and cheer,

Fire sparks up from this, from which water we see.

From water, rock and earth take shape,

A gravitational collapse, we find.

Matter forms, worlds emerge, no escape,

Embodied beings formed in kind.

The colors of the elemental lights,

White, red, blue, green, and yellow too.

Rainbow body, a transformation in sights,

From dense matter, pure light ensues.

Buddhist practices can alter the field,

Of the elements that make up our form.

Radiant lights from the body can be revealed,

Jalu, the Tibetan term for this norm.

Rinpoche reminds us, these powers we gain,

Are mere signs, not the point in the end.

All beings we must serve, this must remain,

Compassion and dedication, our true friend.

Sorcery's risk, if powers are chased,

Infatuation with self, brings pride and hate.

Hide accomplishments, distractions erased,

True Dzogchen practitioners know their fate.

Conscience, the faculty of knowing right,

Awareness of our acts, conforms or not.

From Latin and French, this word takes flight,

In all beings, this moral sense should be taught.

De la cinci elementesuntem

alcătuiți,

Pământ, apă, foc, aer și spațiu.

Vibrațiile ridicate, încet sunt stinse,

Blocurile de construcție ale realității ne aduc în virtute.

În Dzogchen, cosmosul este transparent,

Deschis și luminos până la adâncime.

Vântul se mișcă din aer, ca un părinet,

Focul aprinde, apa vine.

De la apă, rocile și pământul prind viață,

O colapsare gravitațională este la mijloc.

Lumea se naște, creaturi sunt formate,

Fiecare element prezent, în toate locurile se joacă.

Luminile elementelor au culori de vis,

Alb, roșu, albastru, verde, și galben pe deasupra.

Rainbow body, transformare în pură lumină d-a

drept făptuitorul ce a fost vreodată dens,

Prin practică și meditație, atinge punctul de sus pe culmea.

Practica budistă schimbă câmpul de forță,

Al elementelor din care suntem creați.

Luminile radiază prin corp ca un furtună,

Jalu, în Tibetanică, denumirea se regăsește.

Rinpoche ne aduce aminte,

Aceste puteri sunt doar o cale de semn.

Compasiune și devotament, de pe-acum încolo, oricând,

Pentru a sluji tuturor ființelor, fără niciun cuvânt.

Dacă urmăm puterile cu patimă,

Mândria și ura vin la pachet.

Ascunde-ți realizările, fără să le arăți cu naduf,

Pentru a găsi drumul, cel care duce spre

The body of a rainbow, a feat

of transcendence,

Transforming matter to pure light with disciplined ascendance,

Through meditation, altering the gravitational field,

Of earth, water, fire, air, and space, a path to yield.

Jalu, the Tibetan term for physical fluorescence,

Obtained by years of practice with diligent essence,

A supreme accomplishment attained in this life,

Dedicated to the benefit of all beings in sight.

Miraculous feats, by-products of this attainment,

But not the goal, nor an endowment for self-entertainment,

To become infatuated with power, a risk of pride and arrogance,

True practitioners hide accomplishments, avoiding attention and disturbance.

Conscience, a faculty of knowing what is right,

A moral sense, a sense of fairness or justice in sight,

A knowledge within oneself of right and wrong,

A sense of awareness, a sense of belonging.

If conscience is missing, start working on your soul,

Follow the right path, and let your spirit unfold.

Emptiness, Dependent Origination, Compassion, and Sambhogakāya,

The building blocks of reality, leading to a rainbow body's display.

Trupul curcubeului, o faptă

de transcendență,

Transformarea materiei în lumină pură cu ascensiune disciplinată,

Prin meditație, alterarea câmpului gravitațional,

Al pământului, apei, focului, aerului și spațiului, un drum de dezvăluire.

Jalu, termenul tibetan pentru fluorescența fizică,

Obținută prin ani de practică cu esență diligentă,

O realizare supremă dobândită în această viață,

Dedicată beneficiului tuturor ființelor în vedere.

Faptele miraculoase, produse ale acestei realizări,

Dar nu obiectivul, nici o dotare pentru auto-amuzament,

Înfrumusețarea puterii, un risc de mândrie și aroganță,

Practicanții adevărați își ascund realizările, evitând atenția și perturbarea.

Conștiința, o facultate de a ști ce este corect,

O simțire morală, un simț al echității sau justiției în vedere,

O cunoaștere interioară a dreptului și a greșelii,

Un sentiment de conștientizare, un sentiment de apartenență.

Dacă conștiința lipsește, începe să lucrezi la sufletul tău,

Urmărește calea cea dreaptă și lasă-ți spiritul să se dezvăluie.

Văcușenia, Originea dependentă, Compasiunea și Sambhogakāya,

Blocurile de construcție ale realității, conduc la afișarea unui corp curcubeu.

Rainbow Body, pure and bright,

Transformed by Dzogchen's ancient light,

A journey from dense matter to pure energy,

A cosmic dance of elements, ever so elegantly.

Earth, water, fire, air, and space,

Building blocks of reality, in perfect grace,

From these, all things are formed,

Including our bodies, so perfectly adorned.

Under certain circumstances, the collapse of matter,

Can reverse, and the radiant lights will scatter,

Transforming dense matter into pure light,

A physical fluorescence, so beautiful and bright.

Jalu, the Tibetan word for this wondrous sight,

A rainbow body, a miracle of spiritual might,

Years of specific disciplined practice,

A transformation of the ordinary, so fantastic.

True Dzogchen practitioners, humble and kind,

Hide their accomplishments, to focus the mind,

Compassion and dedication, the only way,

To attain enlightenment, without delay.

Miracles and siddhis, mere by-products of the quest,

To achieve ultimate freedom, the ultimate test,

To dissolve karma, and benefit all beings,

Is the true essence of all spiritual teachings.

Conscience, a sense of fairness and justice,

Knowing right from wrong, in all of us,

The path to the Rainbow Body, pure and bright,

Is within us all, just waiting for the right light.

Corpul învăluit de lumină,

Transformare divină,

Prin Dzogchen și-a găsit calea,

De la materie la energie pură, prin strălucirea ta.

Pământ, apă, foc, aer și spațiu,

Bazele realității în armoniu,

Din ele, toate sunt create,

Inclusiv trupurile noastre frumos împodobite.

Prin circumstanțe ce apar,

Procesul poate inversa,

Din materie densă, lumină va răsări,

Jalu, fluorescenta cea minunată.

Cuvântul tibetan pentru acest miracol,

Rainbow Body, transformat dintr-un sol,

Ani de practică și disciplină,

Transformarea trupului, o minune divină.

Adevărații practicanți de Dzogchen,

Sunt umili și înțelegători deplin,

Compasiunea și dedicarea, singura cale,

Pentru a ajunge la lumină fără greșeală.

Miracole și siddhis, nenumărate efecte,

Obținerea libertății, încununarea unui proces perfect,

Dizolvarea karma și binele tuturor ființelor,

Sunt esența învățăturilor spirituale.

Conștiința, o înțelegere profundă și justiție,

De a face diferența între bine și rău, în orice situație,

Drumul spre Rainbow Body, luminos și pur,

Este în noi toți, așteptând lumină și căldură.

Rainbow Body, a path to light

Where matter fades into cosmic might

From air to fire, water to stone

The elements we're made of, alone

In Dzogchen, the world is clear and open

A spiraling dance of elements spoken

The vibratory states slow to dense matter

A building block reality, with no clutter

With meditative technologies reversing the flow

From pure light to dense matter, they show

The transformation of the ordinary body

Into radiant lights, a spiritual prodigy

The jalu, a physical fluorescence, a sign

Of the disciplined practitioner's divine

The merit gained is for the other's benefit

Not for the self, this is the true spirit

Chasing siddhis, without compassion and dedication

Is sorcery, not the path to spiritual elevation

The true Dzogchen practitioner hides their success

To avoid pride and arrogance, they suppress

Conscience, a sense of fairness and justice

The moral compass, the true guide to our trust

A joint knowledge with others, a sense of right and wrong

Conscience, the light that guides us along

Rainbow Body, a path to follow with care

A journey from matter to light, we must dare

With conscience as our guide, we'll reach the divine

And in this life, we'll attain Buddha, it's time.

Corpul de curcubeu, calea

spre lumină

Unde materia se estompează în putere cosmică fină

De la aer la foc, de la apă la piatră

Elementele din care suntem făcuți, sunt toate așezate-ntr-o-oală

În Dzogchen, lumea e clară și deschisă

O dansă spiralică de elemente dezlănțuită

Stările vibratoare încetinesc la materie densă

Realitatea e construită cu lego, fără să fie cu vreo lense

Cu tehnologii meditative, fluxul se schimbă

De la lumină pură la materie densă, se dovedește că e așa cum se spune

Transformarea corpului fizic obișnuit

În lumini radiante, prodigiu spiritual nesperat

Jalu, o lumină fizică, un semn

A practicii disciplinate de un practicant bun

Méritul câștigat e pentru folosul altora

Nu pentru sine, astfel e adevărul din adâncul ființei lor

În urmărirea siddhis fără compasiune și dedicare

Este magie neagră, nu calea spre spiritualitate

Adevăratul practicant Dzogchen ascunde reușita lor

Să evite mândria și aroganța, o astfel de cale îi va înghiti în zbor

Conștiința, un simț al echității și al justiției

Busola morală, ghidul adevărat al noastrei vieți

O cunoștință comună cu alții, un simț al binelui și al răului

Conștiința, lumina care ne ghidează în viață pe drumul nostru de martiriu

Corpul de curcubeu, o cale de urmat cu atenție

O călător

Rainbow Body, a path to

enlightenment,

Dzogchen teachings, a cosmic alignment,

Emptiness, Dependent Origination, Compassion,

Sambhogakāya, a radiant transformation.

The Legos of reality, building blocks of our form,

Earth, water, fire, air, and space, a colorful storm,

High vibratory states, slowing down to matter dense,

A journey of reversal, from light to dense.

Tibetan traditions, meditative technologies,

Alter gravitational fields, transform energetics,

Radiant lights of the color spectrum, a fluorescence,

Jalu, the Rainbow Body, a physical essence.

Years of disciplined practices, a transformation,

Transference and radiance, the ultimate manifestation,

The supreme accomplishment, attaining Buddha in this life,

Dissolution of karma, for the benefit of all in this strife.

Miraculous activities, a mere by-product of achievement,

True Dzogchen practitioners, avoid attention and detachment,

Siddhis without compassion, borders on sorcery,

Conscience, the moral sense, the path to harmony.

Rainbow Body, unification of the cosmic and the earthly,

A path to enlightenment, a transformation of the body,

Inward reflection, outward expression, a journey to the sublime,

A spiritual pursuit, a timeless and infinite paradigm.

Corpul curcubeu, calea

iluminării,

Învățăturile Dzogchen, o aliniere cosmică,

Văcuime, Origine Dependentă, Compasiune,

Sambhogakāya, o transformare radianta.

Lego-urile realității, blocurile de construcție ale formei noastre,

Pământ, apă, foc, aer și spațiu, o furtună colorată,

Stări vibratoare ridicate, încetinindu-se în materie densă,

O călătorie de inversare, de la lumină la dens.

Tradițiile tibetane, tehnologii meditative,

Transformă câmpurile gravitaționale, transformă energia,

Luminile radiante ale spectrului de culori, o fluorescență,

Jalu, Corpul Curcubeu, o esență fizică.

Ani de practici disciplinate, o transformare,

Transfer și strălucire, manifestarea finală,

Realizarea supremă, obținerea lui Buddha în această viață,

Dizolvarea karmei, în beneficiul tuturor în această luptă.

Activități miraculoase, un simplu produs al realizării,

Adevărații practicanți Dzogchen, evită atenția și detenția,

Siddhis fără compasiune, se îndreaptă spre vrăjitorie,

Conștiința, simțul moral, calea spre armonie.

Corpul curcubeu, unificarea cosmicului și a pământului,

O cale către iluminare, o transformare a corpului,

Reflecție interioară, expresie exterioară, o călătorie spre sublim,

O căutare spirituală, un paradis etern și infinit.

The cosmos, transparent and

open wide,

Air and fire in motion, elements collide.

Water and earth, solidity attained,

Worlds formed, embodied beings sustained.

Legos of reality, building blocks of creation,

Earth, water, fire, air, and space, a rainbow formation.

Journey from dense matter to high-vibratory light,

Meditative technologies, Dzogchen's insight.

Transformation of the physical body, a radiant sight,

Jalu, a Tibetan term for fluorescence so bright.

Years of discipline, meditation's path,

To transform the body, a true aftermath.

Transference, the possible way,

Radiance, the path, Rinpoche did say.

Miracles and powers, by-products of accomplishment,

True practitioners hide, avoid any amazement.

Compassion and dedication to freedom, a must,

Siddhis without this, a dangerous lust.

Conscience, a faculty of knowing what is right,

A moral sense, fairness, justice, a guiding light.

A journey to the Rainbow Body, a path to follow,

Emptiness, Compassion, Dependent Origination to swallow.

Dzogchen's wisdom, a way to transform,

From dense matter to pure light, a radiant norm.

Corpul într-un arc en ciel se

transformă,

Prin practici rare, Dzogchen se reformează.

Goliciunea, Compatibilitatea, Originea dependentă,

Și manifestarea divină a Sambhogakāya.

Cosmosul, transparent și deschis,

Aerul și focul în mișcare, elementele colind.

Apa și pământul, soliditatea dobândită,

Lumi formate, ființe întrupate susținute.

Legourile realității, blocuri de construcție ale creației,

Pământul, apa, focul, aerul și spațiul, o formă în curcubeu.

Călătoria de la materie densă la lumină vibrațională înaltă,

Tehnologiile meditative, înțelepciunea Dzogchen.

Transformarea corpului fizic, o imagine strălucitoare,

Jalu, un termen tibetan pentru o lumină fluorescendă.

Ani de disciplină, calea meditației,

Pentru a transforma corpul, un adevărat rezultat.

Transferul, modul posibil,

Strălucirea, calea, a spus Rinpoche clar.

Minunile și puterile, produse ale realizării,

Practicanții adevărați se ascund, evită orice uimire.

Compassion și dedicația libertății, o necesitate,

Siddhis fără ele, un pericolos interes.

Conștiința, o facultate a cunoașterii a ceea ce este corect,

O simțire morală, dreptatea, o lumină călăuzitoare perfect.

Călătoria spre Corpul curcubeu, o cale de urmat,

Goliciune, Compatibilitate, Originea dependentă de îngurgitat.

Înțelepciune

Rainbow Body, oh what a sight,

Formed from building blocks of light,

Five elements in harmony,

Transformed by meditative alchemy.

Earth, water, fire, air, and space,

Combined in a cosmic embrace,

Transcending vibratory state,

Dense matter to pure light, they translate.

Jalu, the physical fluorescence,

Radiant lights of the color spectrum,

A transformation, a discipline intense,

Of the ordinary body to a sacred emblem.

But beware the pursuit of siddhis,

Without compassion and dedication to free,

For true Dzogchen hides their abilities,

And seeks enlightenment selflessly.

Conscience, the sense of right and wrong,

A moral compass, a guide lifelong,

To journey from self to others,

And attain Buddha, as equals and brothers.

Corporeal, ethereal, a divine reflection,

The Rainbow Body, a spiritual perfection.

Corpul, etereal, o reflecție

divină,

Corpul curcubeu, o perfecțiune spirituală.

In fields where nothing grew

but weeds

I found a flower at my feet

Bending there in my direction

I wrapped a hand around its stem

And pulled until the roots gave in

Finding there what I've been missing

And I know...

So I tell myself, I'll be strong

And dreaming when they're gone

'Cause they're calling, calling, calling me home

Calling, calling, calling home

You show the lights that stop me turn to stone

You shine them when I'm alone

And so I tell myself that I'll be strong

And dreaming when they're gone

'Cause they're calling, calling, calling me home

Calling, calling, calling home

You show the lights that stop me turn to stone

You shine them when I'm alone

And so I tell myself that I'll be strong

And dreaming when they're gone

'Cause they're calling, calling, calling me home

Calling, calling, calling home

And I know...

I'll be alright

Translation in Romanian:

În lanurile unde nu creștea

nimic, decât buruieni

Am găsit o floare la picioarele mele

Îndreptată spre mine

Am înconjurat tulpina cu o mână

Și am tras până când rădăcinile au cedat

Descoperind acolo ceea ce îmi lipsea

Și știu...

Așa că îmi spun, voi fi puternic

Și visez când nu mai sunt

Pentru că ei mă cheamă acasă

Mă cheamă acasă

Tu arăți luminile care mă opresc să devin piatră

Le strălucești când sunt singur

Și așa îmi spun că voi fi puternic

Și visez când nu mai sunt

Pentru că ei mă cheamă acasă

Mă cheamă acasă

Tu arăți luminile care mă opresc să devin piatră

Le strălucești când sunt singur

Și așa îmi spun că voi fi puternic

Și visez când nu mai sunt

Pentru că ei mă cheamă acasă

Mă cheamă acasă

Și știu...

Voi fi bine

Rainbow Body, a

transformation so rare,

Attained through practices of Dzogchen's prayer.

Emptiness, Compassion, Dependent Origination,

And Sambhogakāya's divine manifestation.

In Dzogchen's realm of realization,

The rainbow body shines its illumination,

Through trekchö and tögal's devotion,

Practitioners dissolve with pure emotion.

The rainbow body, small and radiant,

Dissolving into space, luminescent,

Garab Dorje, Manjushrimitra,

Shri Singha, Jnanasutra, Vairotsana, they were.