Bigfoot and the Native American Connection

Bush Indian is just one of the names the Bigfoot is known by in the Native

American cultures, the Cherokee know him by Tsul 'Kalu (pronounced - Jutaculla

or Judaculla). Below is the very interesting story of a Cherokee woman marrying

a Tsul Kalu (Bigfoot). Note that the location of the town Kanuga is in my

research area.

A Cherokee Legend of Tsul Kalu (the slant-eyed or sloping giant)

A long time ago a widow lived with her one daughter at the old town of Känuga on

Pigeon river. The girl was of age to marry, and her mother used to talk with her

a good deal.

One day, her mother told her she must be sure to take no one but a good hunter

for a husband, so that they would have some one to take care of them and would

always have plenty of meat in the house.

The girl said such a man was hard to find, but her mother advised her not to be

in a hurry, and to wait until the right one came.

Now the mother slept in the house while the girl slept outside in the âsï. One

dark night a stranger came to the âsï wanting to court the girl, but she told

him her mother would let her marry no one but a good hunter. "Well," said the

stranger, "I am a great hunter," so she let him come in, and he stayed all

night. Just before day he said he must go back now to his own place, but that he

had brought some meat for her mother, and she would find it outside. Then he

went away and the girl had not seen him. When day came she went out and found

there a deer, which she brought into the house to her mother, and told her it

was a present from her new sweetheart. Her mother was pleased, and they had deer

steaks for breakfast.

He came again the next night, but again went away before daylight, and this time

he left two deer outside. The mother was more pleased this time, but said to her

daughter, "I wish your sweetheart would bring us some wood."

Now wherever he might be, the stranger knew their thoughts, so when he came the

next time he said to the girl, "Tell your mother I have brought the wood"; and

when she looked out in the morning there were several great trees lying in front

of the door, roots and branches and all.

The old woman was angry, and said, "He might have brought us some wood that we

could use instead of whole trees that we can't split, to litter up the road with

brush." The hunter knew what she said, and the next time he came he brought

nothing, and when they looked out in the morning the trees were gone and there

was no wood at all, so the old woman had to go after some herself.

Almost every night he came to see the girl, and each time he brought a deer or

some other game, but still he always left before daylight. At last her mother

said to her, "Your husband always leaves before daylight. Why don't he wait? I

want to see what kind of a son-in-law I have."

When the girl told this to her husband he said he could not let the old woman

see him, because the sight would frighten her. "She wants to see you, anyhow,"

said the girl, and began to cry, until at last he had to consent, but warned her

that her mother must not say that he looked frightful (usga'së`ti'yu).

The next morning he did not leave so early, but stayed in the âsï, and when it

was daylight the girl went out and told her mother. The old woman came and

looked in, and there she saw a great giant, with long slanting eyes (tsul`kälû'),

lying doubled up on the floor, with his head against the rafters in the

left-hand corner at the back, and his toes scraping the roof in the right- hand

corner by the door.

She gave only one look and ran back to the house, crying, Usga'së`ti'yu! Usga'së`ti'yu!

Tsul`kälû' was terribly angry. He untwisted himself and came out of the âsï, and

said good-bye to the girl, telling her that he would never let her mother see

him again, but would go back to his own country. Then he went off in the

direction of Tsunegûñ'yï.

Soon after he left the girl had her monthly period. There was a very great flow

of blood, and the mother threw it all into the river. One night after the girl

had gone to bed in the âsï her husband came again to the door and said to her, "It

seems you are alone," and asked where was the child. She said there had been

none.

Then he asked where was the blood, and she said that her mother had thrown it

into the river. She told just where the place was, and he went there and found a

small worm in the water. He took it up and carried it back to the âsï, and as he

walked it took form and began to grow, until, when he reached the âsï, it was a

baby girl that he was carrying.

He gave it to his wife and said, "Your mother does not like me and abuses our

child, so come and let us go to my home." The girl wanted to be with her husband,

so, after telling her mother good-bye, she took up the child and they went off

together to Tsunegûñ'yï.

Now, the girl had an older brother, who lived with his own wife in another

settlement, and when he heard that his sister was married he came to pay a visit

to her and her new husband, but when he arrived at Känuga his mother told him

his sister had taken her child and gone away with her husband, nobody knew where.

He was sorry to see his mother so lonely, so he said he would go after his

sister and try to find her and bring her back. It was easy to follow the

footprints of the giant, and the young man went along the trail until he came to

a place where they had rested, and there were tracks on the ground where a child

had been lying and other marks as if a baby had been born there. He went on

along the trail and came to another place where they had rested, and there were

tracks of a baby crawling about and another lying on the ground.

He went on and came to where they had rested again, and there were tracks of a

child walking and another crawling about. He went on until he came where they

had rested again, and there were tracks of one child running and another walking.

Still he followed the trail along the stream into the mountains, and came to the

place where they had rested again, and this time there were footprints of two

children running all about, and the footprints can still be seen in the rock at

that place.

Twice again he found where they had rested. and then the trail led up the slope

of Tsunegûñ'yï, and he heard the sound of a drum and voices, as if people were

dancing inside the mountain. Soon he came to cave like a doorway in the side of

the mountain, but the rock was so steep and smooth that he could not climb tip

to it, but could only just look over the edge and see the heads and shoulders of

a great many people dancing inside. He saw his sister dancing among them and

called to her to come out.

She turned when she heard his voice, and as soon as the drumming stopped for a

while she came out to him, finding no trouble to climb down the rock, and

leading her two little children by the hand. She was very glad to meet her

brother and talked with him a long time, but did not ask him to come inside, and

at last he went away without having seen her husband.

Several other times her brother came to the mountain, but always his sister met

him outside, and he could never see her husband. After four years had passed she

came one day to her mother's house and said her husband had been hunting in the

woods near by, and they were getting ready to start home tomorrow, and if her

mother and brother would come early in the morning they could see her husband.

If they came too late for that, she said, they would find plenty of meat to take

home. She went back into the woods, and the mother ran to tell her son. They

came to the place early the next morning, but Tsul`kälû' and his family were

already gone. On the drying poles they found the bodies of freshly killed deer

hanging, as the girl had promised, and there were so many that they went back

and told all their friends to come for them, and there were enough for the whole

settlement.

Still the brother wanted to see his sister and her husband, so he went again to

the mountain, and she came out to meet him. He asked to see her husband, and

this time she told him to come inside with her. They went in as through a

doorway, and inside he found it like a great townhouse.

They seemed to be alone, but his sister called aloud, "He wants to see you," and

from the air came a voice, "You can not see me until you put on a new dress, and

then you can see me."

"I am willing," said the young man, speaking to the unseen spirit, and from the

air came the voice again, "Go back, then, and tell your people that to see me

they must go into the townhouse and fast seven days, and in all that time they

must not come out from the townhouse or raise the war whoop, and on the seventh

day I shall come with new dresses for you to put on so that you can all see me."

The young man went back to Känuga and told the people. They all wanted to see

Tsul`kälû', who owned all the game in the mountains, so they went into the

townhouse and began the fast. They fasted the first day and the second and every

day until the seventh-all but one man from another settlement, who slipped out

every night when it was dark to get something to eat and slipped in again when

no one was watching.

On the morning of the seventh day the sun was just coming up in the east when

they beard a great noise like the thunder of rocks rolling down the side of

Tsunegûñ'yï. They were frightened and drew near together in the townhouse, and

no one whispered.

Nearer and louder came the sound until it grew into an awful roar, and every one

trembled and held his breath-all but one man, the stranger from the other

settlement, who lost his senses from fear and ran out of the townhouse and

shouted the war cry.

At once the roar stopped and for some time there was silence. Then they heard it

again, but as if it where going farther away, and then farther and farther,

until at last it died away in the direction of Tsunegûñ'yï, and then all was

still again. The people came out from the townhouse, but there was silence, and

they could see nothing but what had been seven days before.

Still the brother was not disheartened, but came again to see his sister, and

she brought him into the mountain. He asked why Tsul`kälû' had not. brought the

new dresses, as he had promised, and the voice from the air said, "I came with

them, but you did not obey my word, but broke the fast and raised the war cry."

The young man answered, "It was not done by our people, but by a stranger. If

you will come again, we will surely do as you say." But the voice answered, "Now

you can never see me." Then the young man could not say any more, and he went

back to Känuga.

Tsul 'Kalu

Tsul 'Kalu (the slant-eyed or sloping giant), is a legendary figure in Cherokee mythology who plays the role of "the great lord of the game", and as such is frequently invoked in hunting rites and rituals.[1] Tsul 'Kalu is also believed by some to be the Cherokee version of Sasquatch or Bigfoot because he seems to share several physical and behavioral traits with the creature.

The tale is one of the best known Cherokee legends and was recorded by Europeans as early as 1823, often using the spelling, Tuli cula. The name Tsul 'Kalu means literally "he has them slanting/sloping", being understood to refer to his eyes, although the word eye (akta, plural dikta) is not a part of it. In the plural form it is also the name of a traditional race of giants in the far west.[2]

He is said to dwell in a place called Tsunegun'yi. The words

Tsul and Tsune and their variations appear in a number of Cherokee place names

throughout the Southeastern United States, especially in western North Carolina

and eastern Tennessee (much as Sasquatch references appear in the place names of

other tribes).

Tsul`kälû' Tsunegûñ'yï is a 100-acre (40 ha) patch on a slope of the mountain

Tanasee Bald [3] in Jackson County, North Carolina, on the ridge upon which the

boundari of Haywood, Jackson, and Transylvania Counties converge.[1] It is

believed Tsul 'Kalu was responsible for clearing the spot for his residence. The

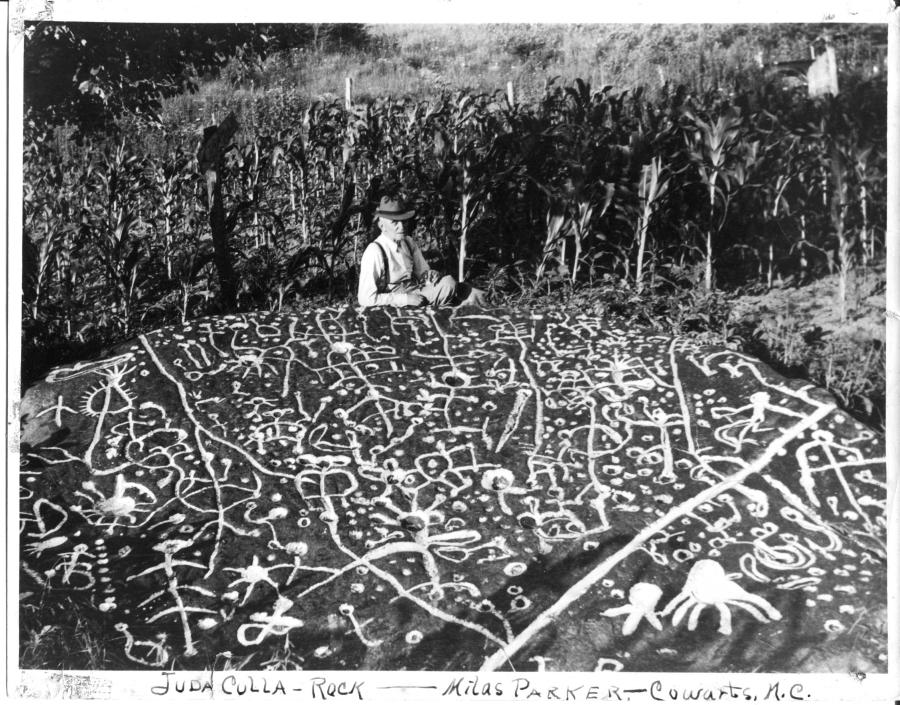

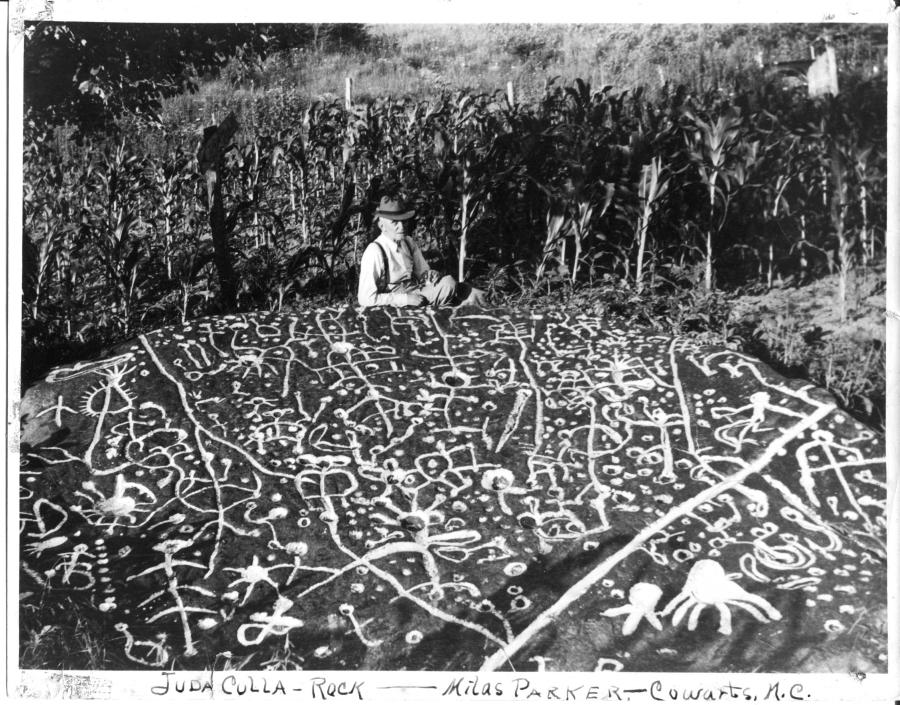

name is sometimes corrupted by Europeans to Jutaculla; consequently the area is

also known as the "Jutaculla Old Fields". There is also a large slab of

soapstone called "Jutaculla Rock" nearby, which is covered with strange

scratches and carvings. These markings are said to have been made by the giant

when he would jump from his home on the mountain to the creek below.[4]

Another place associated with Tsul 'Kalu, Tsula'sinun'yi (literally "where the

footprint is"), is located on the Tuckasegee River, about a mile above Deep

Creek in Swain County, North Carolina. Impressions said to have been the

footprints of the giant Tsul`kälû' and a deer were found on a rock which was

destroyed during railroad building.

A long time ago a widow lived with her one daughter at the old

town of Känuga on Pigeon River. The girl was of age to marry, and her mother

used to talk with her a good deal.

One day, her mother told her she must be sure to take no one but a good hunter

for a husband, so that they would have some one to take care of them and would

always have plenty of meat in the house.

The girl said such a man was hard to find, but her mother advised her not to be

in a hurry, and to wait until the right one came.

Now the mother slept in the house while the girl slept outside in the âsï. One

dark night a stranger came to the âsï wanting to court the girl, but she told

him her mother would let her marry no one but a good hunter. "Well," said the

stranger, "I am a great hunter," so she let him come in, and he stayed all

night. Just before day he said he must go back now to his own place, but that he

had brought some meat for her mother, and she would find it outside. Then he

went away and the girl had not seen him. When day came she went out and found

there a deer, which she brought into the house to her mother, and told her it

was a present from her new sweetheart. Her mother was pleased, and they had deer

steaks for breakfast.

He came again the next night, but again went away before daylight, and this time

he left two deer outside. The mother was more pleased this time, but said to her

daughter, "I wish your sweetheart would bring us some wood."

Now wherever he might be, the stranger knew their thoughts, so when he came the

next time he said to the girl, "Tell your mother I have brought the wood"; and

when she looked out in the morning there were several great trees lying in front

of the door, roots and branches and all.

The old woman was angry, and said, "He might have brought us some wood that we

could use instead of whole trees that we can't split, to litter up the road with

brush." The hunter knew what she said, and the next time he came he brought

nothing, and when they looked out in the morning the trees were gone and there

was no wood at all, so the old woman had to go after some herself.

Almost every night he came to see the girl, and each time he brought a deer or

some other game, but still he always left before daylight. At last her mother

said to her, "Your husband always leaves before daylight. Why don't he wait? I

want to see what kind of a son-in-law I have."

When the girl told this to her husband he said he could not let the old woman

see him, because the sight would frighten her. "She wants to see you, anyhow,"

said the girl, and began to cry, until at last he had to consent, but warned her

that her mother must not say that he looked frightful (usga'së`ti'yu).

The next morning he did not leave so early, but stayed in the âsï, and when it

was daylight the girl went out and told her mother. The old woman came and

looked in, and there she saw a great giant, with long slanting eyes (tsul`kälû'),

lying doubled up on the floor, with his head against the rafters in the

left-hand corner at the back, and his toes scraping the roof in the right-hand

corner by the door.

She gave only one look and ran back to the house, crying,

Usga'së`ti'yu! Usga'së`ti'yu!

Tsul`kälû' was terribly angry. He untwisted himself and came out of the âsï, and

said good-bye to the girl, telling her that he would never let her mother see

him again, but would go back to his own country. Then he went off in the

direction of Tsunegûñ'yï. (Mooney, 1900)

Interessante, ma impreciso.

Tsul 'Kalu significa in realtà una altra cosa.

tsul, skull = cranio, testa

kalu, kali, = nero

Che significa Testa Nera

Possiamo partire da qui, allora, e andare a ritroso....

Jedi Simon